And just like that, July is over halfway done. I’ll admit, I’ve lost track of the summer days passing while waiting for each scorching heat wave to end. This summer is less busy than others in past years, providing lots of opportunities to nature watch from my back porch. From my vantage point, I can often observe the movements of chipmunks and deer in the forest without alarming them. I’ve also become more aware of the Black-capped Chickadee alarm calls that point the way towards a Barred Owl, hawk, or other predator nearby. Gaining this deeper acquaintance with the nature surrounding my home has been one small gift to come out of the chaos.

I hope that you have also found your knowledge of the nature around you deepen. If you still have more exploring to do, the good news is that summer isn’t over yet! August is just around the corner with all the sights and sounds that late summer brings. And it doesn’t take a backyard or unlimited wild spaces to enjoy them either—the tree along your street, your neighborhood park, or even a patch of grass growing next to the side walk all provide spaces to learn more about the other species we share this planet with. In the meantime, if you’re looking for some nature exploration inspiration over the next few days, I highly encourage you to take part in the Vermont Moth Blitz 2020!

This Week on Tech Tip Tuesday

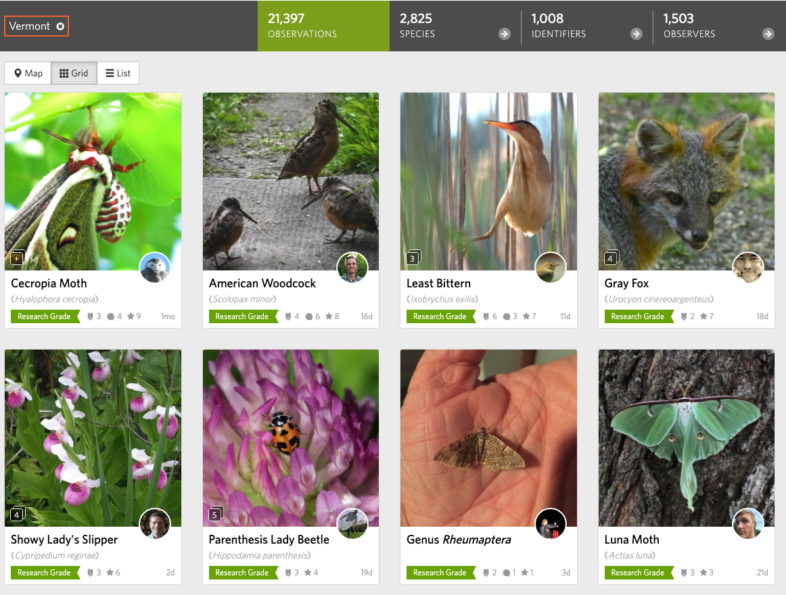

Joining projects and taking part in bioblitzes is a great way to take your iNaturalist use to the next level. Besides providing a place to contribute your observations to a larger collection of information, getting involved with projects is also a great way to connect with a community whose interests are similar to yours. Whether you enjoy documenting cool tracks, the plants in your local town forest, or the animals that visit your backyard, there’s a project out there for you!

First, I recommend spending some time browsing through different projects. You can find the projects page by going to the dropdown menu under “Community” and selecting “Projects”. You can look over the “featured”, “recently active”, and “recently created” projects, or look for others in your interest areas in the search bar.

Once you find a project that interests you, it’s a good idea to officially join it. While you can often contribute to projects without joining, becoming a member will allow you to receive project updates, such as notifications when new blog posts are shared. In some cases, joining the project will allow the project curators (the iNaturalist users running the project) to see your observations’ exact locations. This comes in handy later when they are using the data collected by the project to conduct studies and develop a better understanding of the region. There is no limit on the number of projects you can join and you can leave them any time you want.

To join a project, click on the project that interests you. Once on the project page, you will see text in the top right corner above the project banner that says “Join this project”—click on that. On the next page, you should see the project’s description and below that a list of the curators. Looking further down, you will see a list of project rules. These are the requirements for adding observations to the project. Any observations that don’t meet one of these requirements won’t be accepted to the project. If you continue on, the final section is “Other”. Here, you can select whether you want to receive project updates, like notifications about new blog posts, and whether you want to make private/obscured observation coordinates viewable by the curator(s). As I mentioned above, you should consider changing the privacy settings, since they will allow the project curators to use the observations as data more easily. Once you’re all set, click “Yes, I want to join”.

And that’s it! Occasionally, you may run into an issue where you either can’t add your observation to a project or it doesn’t appear in the project. This could be for a couple reasons. You may not be able to add your observation if the project you’re trying to add to is a collection project. There are different types of projects. Collection projects are the most common type and don’t actually store observations—they simply act as a filtered search. If you go to the project’s page, you should be able to find your observation there by clicking on “View Yours”. In other instances, your observation won’t appear in a project if either the accuracy circle or obscuration box fall outside the project’s place boundaries. Sometimes, you may be unable to add an observation if other rules aren’t followed. For example, if you’re adding an observation to a project like a bioblitz that has specific date requirements, you won’t be able to add observations made outside that date range. So, if you’re trying to add an observation that was made in March, but uploaded in May, to a project that only wants observations from May, you won’t be able to add the observation.

These are just a couple examples of issues you may encounter when uploading observations. If you run into other problems, I recommend searching in the iNaturalist forum to see if other users have encountered a similar issue. Chances are someone else has had a similar experience and will be able to give you some pointers.

TTT Task of the Week

This week, take some time to explore the projects page. If you come across a project that sounds interesting, join it! Keep in mind the potential problems and, when you can’t find an answer, remember that you can always ask for help in the forum!

That’s all for this week. Thanks for helping us map Vermont’s biodiversity, stay safe, and happy observing!